Dentistry at the Museum compares the accessibility of dentistry and the accessibility of art. The goal of the project is to enable a consideration of this parallel by facilitating dental care and an art experience for different publics. It manifests as two mobile dental clinics parked in the museum courtyard providing emergency and routine dental care to underserved populations from the Museum’s neighborhood. Next to the two mobile clinics in the courtyard of the museum, a waiting room is set for people preparing for treatment and for recovery afterwards. The waiting room also serves as a venue for the distribution of the zine created by the volunteers for the project, as well as the site of the collaborative-radio. All members of the public are invited to sign up to DJ a small block of time over the radio. That audio is played inside the clinics during treatment.

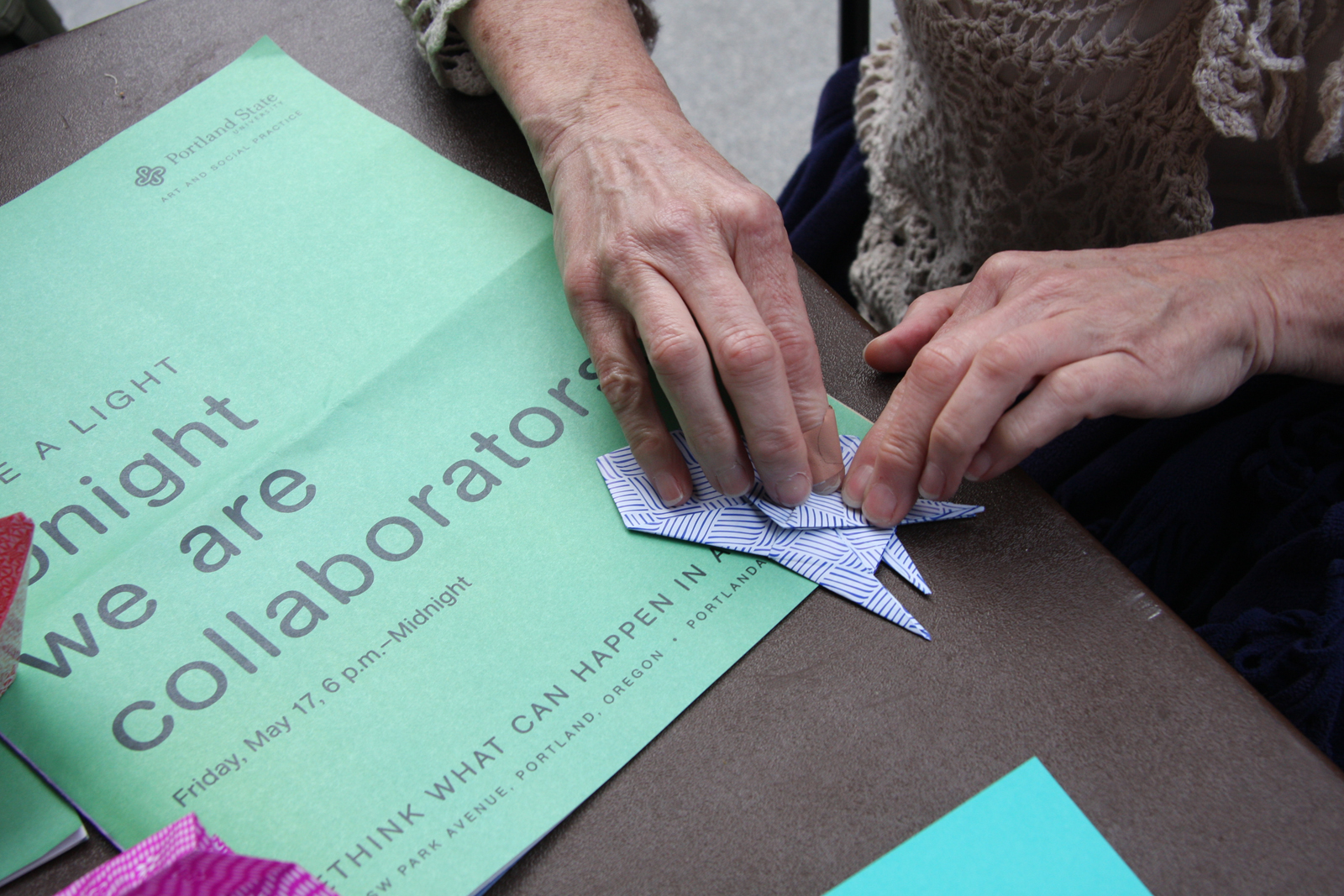

May 17th, 2013. Shine a Light, Portland Art Museum.

This project is in conjunction with Shine A Light, an event put on by the museum and the PSU Art and Social Practice MFA program that questions what is possible in a museum, and Open Engagement, a conference on Socially Engaged Art.

ART IS GOOD FOR YOU

One measure of an artwork is its impact on the people who experience it. If in the Portland Art Museum tonight you see a painting that moves you, or a sculpture that angers you, or a gesture that makes you think differently, then that artwork has impacted you. But beyond evoking strong reactions, how much can an artwork matter? How far can this impact go? To what extent can an artwork change our lives? My artistic practice has followed a line of questioning that explores what makes some artworks matter more than others. This investigation has helped me to find a collection of ideas that I hold as fundamental pillars of my art practice: Meaningful art responds to the political, historical, social climate of its site; meaningful art blends the roles of audience, participant, collaborator and artist; art is something we do together, whether you like it or not; things are often just clutter; meaning is not owned, bought or sold; meaningful art benefits many people, not just the artist; meaningful art is often found outside art galleries. To build on this list, I’ll present and compare Service Media and Useful art, two recent theories that respond to developments in contemporary socially engaged art practices that illustrate to what extent an artwork can change our lives, then show how Dentistry at the Museum supports them.

Dentistry at the Museum compares the accessibility of dentistry and the accessibility of art. The goal of the project is to enable a consideration of this parallel by facilitating dental care and an art experience for different publics. It manifests as two Medical Teams International mobile dental clinics parked in the museum courtyard, one of which provides emergency dental care to underserved populations from the Museum’s neighborhood, the other gives on-site teeth cleanings to the lucky winners of a draw of museum goers. Next to the two mobile clinics in the courtyard of the museum, a waiting room is set for people preparing for treatment and for recovery afterwards. The waiting room also serves as a venue for the distribution of the zine created by the volunteers for the project, as well as the site of the collaborative-radio. All members of the public are invited to sign up to DJ a small block of time over the radio, or dedicate a song to patients receiving treatment. That audio is played inside the clinics during the piece.

In the introduction to Service Media, a collection of writings about socially engaged art practices, editor Stuart Keeler presents Service Media as a sub-classification of these broad social practices. He says “Service Media projects do not glorify the artist as a magical solver of an issue [but] each audience member can experience an urban or civic need or issue and arrive at their own understanding of the topic or situ- ation through the service or performative gesture offered by the artist” (1). Well, this is precisely my ambition for Dentistry at the Museum, to provide a service and enable a consideration of the issues related to the is- sues pertaining to the service. The second idea, the assertion that art can be useful, comes from artist Tania Bruguera. In her Introduction to Useful Art, Bruguera says “Useful Art is a way of working with aesthetic experiences that focus on the implementation of art in society where art’s function is no longer to be a space for “signaling” problems, but the place from which to create the proposal and implementation of pos- sible solutions”. She goes on: “the utilitarian component I’m looking for does not aim to make something that is already useful more beautiful, but on the contrary aims to focus on the beauty of being useful” (2). For someone like me, interested in making art that is inherently meaningful, the attraction to this idea is evident. Where Keeler’s Service Media provides a service related to an issue, Bruguera’s Useful Art goes as far as proposing a possible solution to the problem at hand. In this the ideas vary, but it’s not too much of a stretch to say that they are getting at the same thing: Art actually helps, and helping is a beautiful thing.

The people who receive dental treatment during Dentistry at the Museum will leave, I hope, a little better off than they were before. Furthermore, they will have gained access to dentistry and to the museum despite the systems that normally do little to include them. In my ideal scenario for the project everyone would walk away having received professional teeth cleaning at the museum, because dentistry is a universal need, and because the museum should serve everyone. Too often, museums exclude people who lack the ability to pay entry fees or the ability to gain the education necessary to understand the wealth of culture within the museum’s walls. Unfortunately, this project will not solve the dental crisis in Portland, nor will it open the doors of culture to all of its citizens. But I hope those of us who experience this project will have a chance to think about these issues, having experienced an artwork that makes a real step in the right direction, that actually helps. Dentistry at the Museum embodies an action: it lives as a proposed system wherein people come for art and receive dentistry, and where people come for dentistry and receive art; a system where the institutions of art and dentistry serve the community instead of shutting them out.

At another angle, in relation to Bruguera’s understanding of the beauty of something useful, this project shows the tireless work of the Medical Teams International Mobile Dental Program as a beautiful thing. MTI creatively alleviates a huge social problem. Hundreds of MTI volunteers put on dozens of clinics every week providing “free or low-cost dental care to low-income children and adults, the homeless and migrant workers who lack insurance or a realistic way to pay for treatment. [They] have 12 Mobile Dental clinics in Oregon, Washington and Minnesota. Since 1989, [MTI] has helped 211,493 adults and children through their Mobile Dental program” (3). If artworks can provide a service, if they can be useful, I think the work of MTI belongs in the halls of the art museum, an institution that is to present cultural work that matters so dearly to society.

Beyond this project specifically, artists are actively making work that seeks to serve the community in tangible ways. For the insti- tutions that represent the cultural work of these artists the doors are now open follow suit and invest in tackling the large problems facing their communities.

References

1. Keeler, Service Media: Is it public art, or art in Public space? (Chicago: Green Lantern Press, 2013) p3.

2. Bruguera, Tania, Useful Art. http:// www.taniabruguera.com /cms/528-0- Introduction+on+Useful+Art.htm 2012.

3. Medical Teams International Mobile Dental Clinic website: http://www.medicalteams.org/ what_we_do/dental_program.aspx